|

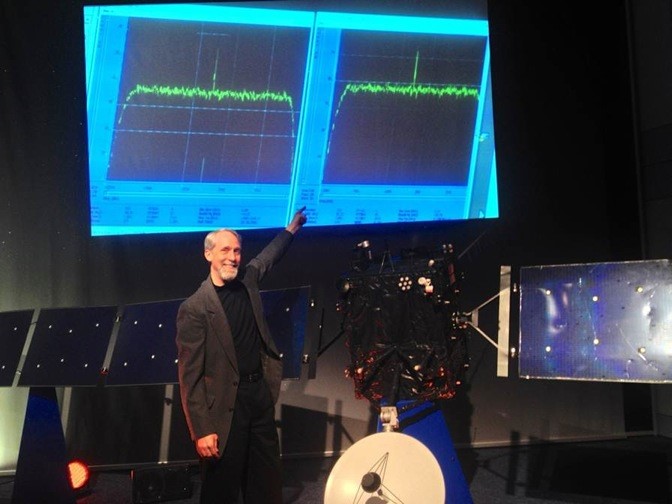

When he moved back to Boulder in 1992 Dr. Parker began working more on studies of solar system objects such as comets, the Moon, asteroids, and Kuiper belt objects. In addition to being the Deputy Principal Investigator for the Alice ultraviolet spectrometer instrument on the Rosetta mission, he is a co-investigator on the New Horizons mission to Pluto, and project manager for the ultraviolet spectrometer on that mission and previously the project manager for a similar instrument on the Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter mission. He is editor of the "Distant EKOs: The Kuiper Belt Electronic Newsletter", is a musician and actor, and can regularly be heard Tuesday mornings on the science show “How on Earth” on radio station KGNU in Boulder/Denver. The photo was taken at ESA's European Space Operations Centre in Darmstadt, Germany. The model of the Rosetta spacecraft that Joel is standing next to is 1/4 scale size. The screen shows the wakeup signal that was received from Rosetta after more than 2.5 years of deep hibernation! |

|

Throughout history, comets have been of great interest to scientists and the general public. They were mysterious, ephemeral objects that, like planets, move in an otherwise unchanging celestial sphere, but unlike planets they would suddenly appear, brighten, grow glorious tails, then fade to apparently disappear forever. In past centuries comets were thought to be signs of the fall of nations, the death of kings, impending war, and disease. Aristotle argued comets were hot, dry exhalations gathered in the atmosphere and occasionally burst into flame. Even in more recent times they were seen with a sense of awe and fear: when Halley's comet appeared in 1910 the public was frightened by the pronouncements that the Earth would pass through the comet's tail of poisonous cyanogen gas, and today we grapple with the real concern that comets can and do collide with the Earth from time to time. As scientists began to study comets they discovered that they were messengers from deep space, providing us with valuable information about the history of our solar system. Comets are some of the leftover debris from the formation of planets, and they provide ways to understand what the content and environment of the solar system was like billions of years ago. Comets have been kept in deep freeze in reservoirs like the Kuiper belt and the Oort Cloud, so they can be used to study those distant reaches of our solar system. They also are a source of water to the planets in the inner solar system such as Earth. For these reasons, comets have been the target of study by scientists using ground- and space-based observatories. Now, the European Space Agency's Rosetta mission, one of the most exciting and challenging space missions to date, will visit a comet and fly along to study it for an extended period of time, and even drop a lander on the comet's surface. Rosetta will arrive at comet Churyumov-Gerasimenko in August of this year after flying more than a decade in space to catch up with the comet. In this Cafe Scientifique, we will start with an overview of the Rosetta mission, the spacecraft and lander, the science that will be done, and the complex operations it takes not just to get there but also the difficulties of spending more than a year in the life of a comet as it passes the Sun. Two good sites related to the Rosetta mission, from the European Space Agency, and from NASA.

|

Dr. Joel Parker is a Director in the Boulder office of Southwest Research Institute. He has B.A. degrees in Physics and Astrophysics from the University of California, Berkeley, and a Ph.D. in Astrophysics from the University of Colorado, Boulder. He worked at NASA's Goddard Spaceflight Center studying hot, massive stars in neighboring galaxies using observations from ground-based observatories around the world as well as the Hubble Space Telescope, the International Ultraviolet Explorer spacecraft, and the Ultraviolet Imaging Telescope that flew aboard the Space Shuttle.

Dr. Joel Parker is a Director in the Boulder office of Southwest Research Institute. He has B.A. degrees in Physics and Astrophysics from the University of California, Berkeley, and a Ph.D. in Astrophysics from the University of Colorado, Boulder. He worked at NASA's Goddard Spaceflight Center studying hot, massive stars in neighboring galaxies using observations from ground-based observatories around the world as well as the Hubble Space Telescope, the International Ultraviolet Explorer spacecraft, and the Ultraviolet Imaging Telescope that flew aboard the Space Shuttle.